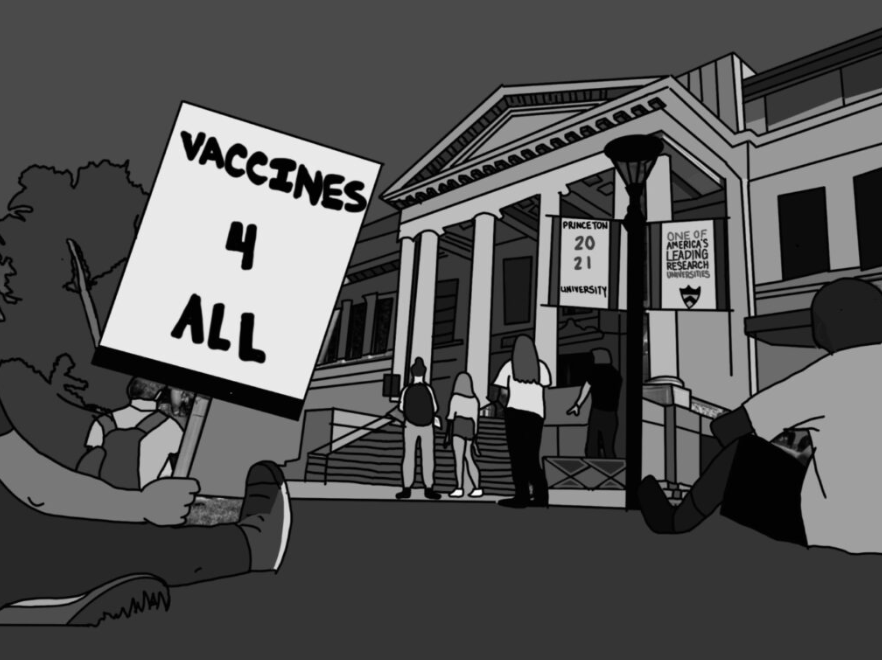

On Saturday, February 13, close to 200 protesters gathered outside of Nassau Hall. On banners and picket signs, they wrote their grievances and demands to Princeton University in regard to its lack of aid to residents during the coronavirus pandemic. Undergraduates, graduates, and residents all braved the afternoon cold to call for Princeton University to share its contact-tracing, testing, and vaccination resources with the residents of the larger Princeton area and to demand that the wider community have greater say in the university’s COVID-related decisions. In response to the protest, a Princeton spokesperson told the Daily Princetonian (2021) that “Princeton can — and is — making a difference during this pandemic through its research and teaching, not by becoming a healthcare provider.” Yet the latter is precisely what the university needs to be to help the townspeople in the best manner.

Princeton University is inextricably tied to Princeton. The town has provided restaurants, gathering places, libraries, and grocery stores for college students to use, thus playing a vital role in sculpting the culture and social life of Princeton University. The university has been essential to the town as well. Teens often go to the campus to hang out after school. The student body of the university drives the local economy. Princeton University would not be the institution that it is without Princeton, and vice versa. By providing COVID-related resources to only students and faculty members and excluding the wider town, the university fails to protect its community.

Given that the university is also endowed with tens of billions of dollars and has recently built its own state-of-the-art testing facility, it has an obligation to lend a helping hand to the people of Princeton. It wouldn’t be the first institution to help its neighborhood either; both the University of California, Davis and Tufts University have partnered with their local governments to do so. UC Davis has provided thousands of tests weekly to its community. Graduate students were trained in contact tracing, and free quarantine housing was provided for citizens who were exposed to the virus. Tufts has provided widespread testing resources to the public school systems of multiple surrounding counties. Princeton University must follow suit. The resources provided by Mercer County aren’t enough to keep the people of Princeton or any town completely safe. Backlogs at clinics due to high demands for testing can make the wait for test results as long as a week, preventing people from going to work and increasing the risk of further spreading. Individuals with full work schedules and members of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups may not be able to access available testing locations. For undocumented and underinsured people who have the hardest time accessing public COVID resources, tests and extra vaccines from the university could be especially valuable. Princeton University is one of the wealthiest schools in the country; it should be actively seeking out ways to help the surrounding areas through the worst health crisis seen so far in this century. In doing so, the university would save local businesses, help community school districts reopen safely, and keep people safe.

Graphic by [credit name="Karen Qiu"]

The new testing laboratory built by Princeton University is capable of handling 10,000 samples a week, but instead handles around 2,000 samples weekly. By building a high-capacity testing laboratory, Princeton University has already become a capable healthcare provider. It is only a matter of whom the university decides to protect. Right now, it has decided not to protect the rest of the community, and it must change this by getting a permit to share its testing capacity. A step like that would be the right direction toward helping others and wouldn’t affect the school’s mission.

The spokesperson also said that Princeton University has already done things to help the town such as “storing [vaccines] in [its] specialized cold storage facilities, hosting community clinics on campus… and assisting with the staffing of these clinics.”

Yet its past collaborations with Princeton officials in storing vaccines and staffing clinics don’t prove that the university has done enough for the surrounding community. Instead, they prove that it has the moral and financial capacity to assist the others despite it not being of any relation to teaching and research. If Princeton University has the capacity to lend its facilities and staff to the community, it should also share testing, contact tracing abilities, and vaccines when they arrive.

If the university truly believed in collaborating closely with the wider community on COVID-related issues, it would have acted on the grievances of the Nassau Hall protesters. Residents are very clearly angry with the university’s pandemic policies, and rather than dismissing the discontent, Princeton University should seriously consider their demands.